- Home

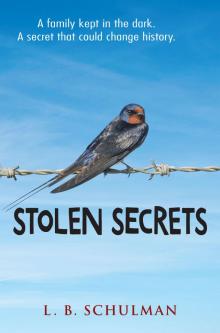

- L. B. Schulman

Stolen Secrets

Stolen Secrets Read online

Text copyright © 2017 by L. B. Schulman

All rights reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. While Anne Frank is a historical figure grounded in historical facts, materials and scenes in this book about or involving Anne Frank have been fictionalized. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events, places, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, please contact [email protected].

Boyds Mills Press

An Imprint of Highlights

815 Church Street

Honesdale, Pennsylvania 18431

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-62979-722-9 (hc) • 978-1-62979-919-3 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937877

First ebook edition

H1.0

Designed by Barbara Grzeslo

Text set in Janson

To my children, who were born when this was a seed of an idea and helped give it life so many years later

APRIL 1945,

BERGEN-BELSEN

CONCENTRATION CAMP

The naked limbs of the dead blocked her path. She tried to step over them, but the disease had weakened her knees, and she buckled to the ground like an enemy plane shot from the sky. Her gaze landed on the vacant stare of a prisoner, bony arm extended as if to invite her into death. That’s when she noticed she’d ripped off her own dress in a fit of fever. All she had left was an envelope, crushed in the grip of her hand. She thought to herself: Hold tight! No one must have it!

Later she woke to a ruckus. Soldiers swarmed the yard. The one with a beret clasped a cloth to his nose. A Brit folded over his gun and vomited. She didn’t comprehend, couldn’t tell her enemies from her saviors.

The soldiers searched for movement among the still, dragging life from the remains.

Save me! she longed to shout. Can’t you see I’m alive? My skin holds the blush of fever! Her mouth was too parched to speak. The words held captive in her head.

With tremendous effort, she raised one hand from the ground, cradling the envelope to her chest with the other. Over here! Her fingers waved like grass in the breeze, except there was no grass in this place. No plants at all. No colors of spring. Only the murky gray of crushed rock and waxy skin under an unremarkable sky.

Darkness bled through her vision. Then God, in an unexpected act of mercy, swaddled her in silence.

CHAPTER

ONE

THE FLOORBOARD UNDER MY FEET RATTLED AS IF THE truck was going to disintegrate.

“Mom, slow down.” My fingernails were deep in the faux leather seat of the U-Haul.

A sign welcomed us to Sacramento. I told myself that after a week on the road, I could handle two more hours.

Mom swerved around a car and then pulled back into the lane. I waved my fingers in front of the rearview mirror, hoping the driver could see my apology in the dim light. According to Road & Travel Magazine, 37 percent of aggressive driving incidents involve firearms.

“This truck has a blind spot bigger than Montana,” I told her. “You should look over your shoulder.”

“Sorry, got lost in my thoughts.”

She’d said the same thing yesterday, after heading twenty miles in the wrong direction on Route 257.

Last week she’d been bouncing around the house, chatting about the joys of city life, the thrill of change, new adventure. Now she seemed untethered. I knew she had a big job interview in a few days, but unlike me, Mom wasn’t the anxious type.

I know you’re upset about the move, Liv, Mom’s AA sponsor had told me as we’d heaved the last box into the van. Try to be supportive of your mom, at least until she finds her people.

Tom was worried about Mom drinking again, I knew it. She’d been sober for five years. I guess it was his job to point out the rocks in her path so she didn’t stumble.

I tapped my jeans pocket, checking that the list of Bay Area AA meetings was still there. “If this interview thing doesn’t pan out, do you think we can go back to Vermont?”

Several seconds passed before Mom said, “San Francisco’s a culinary hot spot, Liv. I could throw a dart and land a job.”

I sighed. She didn’t care that I’d left behind friends I’d had since preschool. Wherever I’d gone, a hand had waved me over. My social life really took off when I started dating the only boy who’d ever liked me back. In May, Sean was voted Hottest Guy in the sophomore class. By association, I ranked top ten. Higher than I deserved—and meaningless, really—but it still made me happy.

“I miss Candace and Audrey. I really miss Sean,” I said now.

“Long-distance relationships don’t usually work out, hon.”

Her cavalier comment was like a whirlpool, sucking me under. It took the screech of brakes to shoot me back to the surface. Our truck had stopped less than a foot behind a minivan with stick-family decals on the back windshield. Cat and dog, too. Mom took her hands off the wheel to stretch her arms behind her head. “Oops,” she said.

“I can take over if you need a break,” I said. The moon blanched in the brightening sky. It was almost dawn. Good thing, because I hadn’t practiced night driving yet.

She shook her head, unbrushed hair settling like tumbleweed on her shoulders. “You just got your learner’s permit, Liv.” Letting go of the wheel again, she transferred a ponytail holder from her wrist to her hair. Our van veered to the left. She adjusted back with her thigh.

I turned to the window. Hill after hill flashed past, carpeted in sun-fried grass. We passed a sign: Capitol Inn, Affordable Comfort at $54.99. According to the bank app, we had three thousand dollars left after giving our new landlord first and last month’s rent with deposit. I knew we couldn’t afford a motel—especially not this close to our destination.

“Maybe we should get some sleep,” I said anyway.

Mom drove past the exit without comment. The eyes of an opossum caught our headlights. “Watch out!” I called.

Too late. She’d flattened it.

“Already dead,” she said with a shrug. “You know, you’re going to like San Francisco, Liv. There’s a farmer’s market on every corner. Everyone’s vegan there.”

Out of 837,000 people, none of them ate meat? It made me crazy when Mom made up stuff, but with an hour and twenty-nine minutes left, I let it go.

“I need coffee,” she announced.

This was her seventh espresso in twenty-four hours, not that I’d been counting. Frustration broke through. “Too much caffeine causes neuron activity, which triggers the adrenal glands into releasing stress hormones,” I blurted out.

Raindrops splashed on the windshield. Mom hit the turn signal, then flashed the headlights before finding the wipers. Drowned bugs smeared across the glass.

“You know, Liv, you should put that photographic memory to better use than acting like a know-it-all. If you don’t look at the heart of the matter, you’ll miss the complexity of the … of the …” She floundered, searching for something that made sense. “Take the psychological impact of coffee, for example. It makes a lot of people insanely happy. I bet you won’t find that in your Scientific American.”

I nodded, tired of the tension that had plagued us through twelve states. I searched the GPS for a place that might be open. It wasn’t working again, so I checked my phone. “I think there’s a Starbucks off exit sixty-seven.”

Mom swerved to the right as if it weren’t four exits away. I nudged my thoughts in a better direction. With the three-hour time difference, school back home had officially started. I’d already missed forty-five minutes of my junior year. I pictur

ed Sean moping through the hallways without me. I glanced at my phone for the hundredth time since we’d left and maxed the volume so that even the car three lanes over couldn’t miss my incoming texts.

Mom found the exit. The lonesome Starbucks glowed like a spaceship on a desolate field. She parked the U-Haul between two compact spaces. “I’ll take a double macchiato, please,” she said, fishing coins from the ashtray.

I wanted to dump the money back into her lap, but Tom’s warning echoed in my head. I climbed down from the truck and headed inside. As I waited for her order, I glanced at my reflection in the polished espresso machine. Without my flat iron, my blond hair had separated into tufts of frizz.

My heart lunged at the muffled chirp. Thoughts of my mother flew from my head as my hand shot to my pocket. Miss you so much!!! I hoped the text would say. Sean wasn’t an exclamation point kind of guy, but it was my fantasy, and I was sticking to it.

Oh, it was Audrey. Hey Liv, was getting a muffin at Gourmet City. Saw there was a help-wanted sign for a manager. Weird. Thought your mom was laid off.

My stomach tightened a notch. I guess things are better now, I texted back. Mom had been Employee of the Month three times at Gourmet City. Why would they lay her off only to hire someone else right away? I searched through my emojis, picking the toothy-grin face with heart eyes. Wish I were with you guys, I wrote. Miss you a ton.

The radio silence didn’t stop me from checking six more times. I hoped she hadn’t gotten caught texting in class.

Back in the truck, Mom blared Queen’s “Fat Bottomed Girls” from the tinny speakers. As she reached for the espresso, the purple wrap bracelet that I’d given her for Mother’s Day slid down her forearm. “One day at a time,” it said. She never took it off, not even in the shower. A fact popped into my head: 90 percent of alcoholics who quit drinking have a relapse before achieving long-term sobriety.

Mom “fell off the wagon” when I was eleven. Only once, and only for an hour.

“I’ll never touch another drop,” she’d promised the next day.

I’d believed her in Vermont. I could believe her in California, too.

“Livvy, wake up!”

A bag of peanut butter–filled pretzels landed in my lap. Breakfast, Mom-style.

My eyes stung, assaulted by sunlight. Before my vision cleared, my ears knew where we were. Honking cars, a truck beeping in reverse, sirens spilling through the streets. Our truck was sandwiched between two buildings that scraped the turquoise sky. San Francisco was loud, bold, and in my face. I put my sunglasses on.

A bicyclist, going twice as fast as us, shot around our U-Haul. Mom grumbled “messengers” before turning left. The next thing I knew, we were climbing the steepest hill I’d ever seen. All of our stuff slid down the truck bed and slammed into the rear door.

“This is California Street!” Mom announced. “Isn’t it gorgeous? We’re going a little out of our way, but I wanted you to see an authentic San Francisco street—one of the longest in the city.” She slowed at the flashing red lights on a brief plateau before we went higher. We were on a roller coaster, cranking to the inevitable drop.

And then the ground rumbled. I grabbed the dashboard. An earthquake? No. The noise was coming from behind. In the passenger side mirror, I watched a real cable car motor up the silver tracks embedded in the road. It was gaining on us.

Finally Mom turned off the street. But now we were pointing down. The junk in the van changed directions, hitting the partition behind our heads. I squeezed my eyes shut.

When we finally leveled off, Mom said, “Thought you could use a wake-me-up.” She pressed her lips together, holding back a laugh.

I tried to frown but couldn’t pull it off. This felt better, like how it used to be. I relaxed into the vinyl seat.

As we cut through the city, she pointed to a row of Victorian houses. They looked glued together, one after another. “Where are the yards?” I asked, thinking about the hundred-year-old maple tree outside the window of my old room. It would change colors any day now. I loved spinning on the tire swing, my head cranked back to gaze at a canopy of red and orange.

“Probably in the back,” she said.

A minute later, we reached the top of a busy street, flanked by people heading to work. Our van crawled down the hill, brakes whining. My head jerked from left to right. There were hip clothing stores and a café on every block and restaurants with outdoor tables. Even a place to get your eyebrows waxed.

Mom looked at me, full of expectation. “This is Fillmore Street. Our neighborhood. What do you think?”

I didn’t know what I thought. A fun place for a vacation? It wasn’t home. Couldn’t be, not as long as Vermont was on the map.

That’s when I noticed that the GPS was still on the blink. “Hey, how do you know your way around?” I asked her. Mom had told me she’d never been west of the Denver ski slopes.

Her head swept the street, searching for an elusive parking space. She cursed at a motorcycle tucked between two cars, as if we could fit our clunky vehicle into the space. “Tom made sure I knew the directions before we left.”

“He used to live here?”

“Yes, in college, I think.”

Abruptly the street ran out of money. The stores looked shabbier; the sidewalks dirtier. At a red light, I stared at a homeless man crouched in front of a Mexican take-out restaurant with an Out of Work sign propped against his foot. I thought about my own jobless mother. What if her restaurant interview fell through? What if she dug in her heels and refused to leave San Francisco? The money we had left wasn’t much of a safety net.

She pointed to a decrepit row of windows on the second floor above a food market. “There it is! That’s our apartment!”

Mom pulled the U-Haul onto our concrete front yard. A dog had left us a housewarming gift.

Home sweet home.

CHAPTER

TWO

MY ARMS FELT WORKED OVER BY A TAFFY MACHINE. I surveyed the moving boxes that littered the studio apartment. Thank God we didn’t have to lug too much furniture up the two flights of stairs.

We can’t bring anything that won’t fit into the U-Haul, Mom had said. She’d invited her AA friends over for a farewell party, insisting that everyone take at least five “party favors” to remember her by, including our ’50s chairs, the dining room table, and the bedroom set that Dad had bought me the summer he moved out.

I wished we’d had a garage sale. We could have made some money.

Sweat snaked down Mom’s neck. She opened her arms, dropping a box to the floor. FRAGILE it read on the side.

“Got to rest,” she announced, collapsing onto the couch.

“So, when’s your interview on Monday?”

“Eight thirty.”

“School’s over at three. How about we celebrate your new job?”

“Or we can celebrate your first day at school,” she said, adding, “There’s one last box. Would you grab it? I’m beat.”

I dragged myself downstairs. A policewoman stood behind our van, writing a ticket.

I pointed to the “U-Haul” emblazoned on the side. “We’re new here.”

“Parking on the sidewalk is illegal everywhere.” She handed me the ticket. Eighty dollars! Where else were we supposed to unload our truck? There wasn’t enough room in this city. Too many people, too many cars.

In my hometown, the city council had voted 6 to 1 against installing downtown parking meters. They wanted to welcome visitors, not scare them away. I clomped back up the stairs, a box of dish towels under one arm, and handed Mom the ticket without a word. She folded it into a paper airplane and aimed for a dust bunny.

Fifteen minutes later, we were on our way to a neighborhood called South of Market to return the U-Haul. Mom cursed at all the signs that didn’t let us turn left. After we dropped the van off, we took an expensive cab ride back to our new neighborhood.

In the apartment, I made our inaugural meal: spaghetti topped with Pau

l Newman’s marinara sauce, purchased from the market under our living room. Cost: $7.28.

Monday seemed a long way away.

We spent the weekend in San Francisco doing touristy things. First stop, Fisherman’s Wharf, where Mom and I shared an enormous bread bowl filled with clam chowder. After that, she insisted on buying me a T-shirt that claimed, I love Frisco!

“It’s $3.99,” she said. “We can’t ignore a deal like that.”

As soon as she found a place to fuel her caffeine dependency, I returned the shirt but kept the bag so she wouldn’t know.

When we reached Pier 33, Mom pulled a pair of tickets out of her purse. I glanced at a ferry with “Alcatraz Cruises” splayed across the front. “I got them on the website,” she said. “You should be happy. Buying them in advance saved us, like, six dollars.”

The chowder threatened to come up when I saw the ticket price. Thirty-three dollars each! Almost as much as that stupid parking ticket.

“You can’t give them back if you order online,” Mom said, looking smug.

I forced a smile. “You got me.”

On Sunday we went to Haight-Ashbury, where the hippie culture still had a pulse.

“Look, Liv!” Mom pointed to a thrift shop. “It’s just like that store that you and Candace always went to.”

Actually, with the cropped vests and peasant blouses, it was an upgrade. I wasn’t going to admit it, though. I wanted to go inside, but I couldn’t. And not because of Mom. A homeless woman sat on a step beside the entrance. She cradled a baby, bundled in a blanket. A sign, tucked between her bare feet, read, God bless those that help.

She caught my eye. “Do you have money for me and my newborn?”

Mom acted like she hadn’t heard. She kept on talking as if the woman didn’t exist. Then she ran ahead to find a bathroom, leaving me alone on the sidewalk.

“I’m sorry,” I began. “I mean, I can’t give you … but …” I thrust my bagel at her. I was hungry, but probably not as hungry as them.

As the woman tried to grab it, the blanket fell to the side. My gaze pulled to the unblinking infant. Torn between empathy and disgust, I stared at the painted face of the one-armed plastic doll. I dropped the bagel in the woman’s lap and took off, my eyes on my shoes, until I caught up with Mom.

Stolen Secrets

Stolen Secrets