- Home

- L. B. Schulman

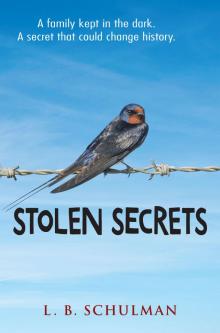

Stolen Secrets Page 2

Stolen Secrets Read online

Page 2

Back at the apartment, I said I wanted to go to bed early, tomorrow being the first day of school and all. Mom seemed to buy my noble reasoning. Truth was, I was wiped. The city was loud and bright and colorful and overwhelming. My senses were amped up from urban assault. What I really wanted was to be swaddled in the green cocoon of my Vermont backyard, but that wasn’t going to happen.

The living room was now Mom’s bedroom. I had to sleep in the walk-in closet opposite the front door. Quarters were tight, but right then, there was something oddly comforting in being able to touch the walls on either side of my blow-up mattress. It reminded me of the old refrigerator boxes that Candace, Audrey, and I used to drag down the street from the appliance store the summer before sixth grade. We spent all our time in there, sharing nothing and everything at the same time—before boys and parties and homecoming dances became more important than spending time together.

I put the flashlight on the shelf and turned on my ancient laptop, waiting for the display to limp to life. Mom’s resume, which I’d transferred to my hard drive the day we’d left, was riddled with errors and inconsistent formatting. Two hours later, I saved the new and improved version, documenting her journey from banana walnut muffins at a supermarket to napoleons at Gourmet City. It wasn’t that much of a leap to see her as a head pastry chef at a hot, new restaurant. Anyone could tell she was a hard worker—at least when it came to baking.

I loved the new resume. It was perfect. I sent it to the printer. Stretching out my hands, I brushed my fingertips along the walls and smiled in the dark.

Early the next morning, as I shuffled into the kitchen for a glass of water, something stuck to my heel. I peeled off a Post-it. 2846 Fillmore Street, it said, circled twice. Mom’s interview address, probably. I put it on the coffeemaker so she wouldn’t miss it.

My thoughts switched to the first day of school. Grant High was huge—four times as many students as at my old school. At least I’d found a map on the website to mark my classrooms. What should I wear? And how many layers? Mom told me that each neighborhood had its own climate. Apparently Noe Valley was the hot spot, but right now it was cold enough for gloves. I sighed. My weather app was useless here.

I unplugged my phone from the charger, hoping to find a string of texts. Despite the three-hour time difference, there was nothing. I didn’t get it. Sean, Candace, and Audrey knew it was my first day. I’d even posted yesterday to remind them.

Using the tiny mirror next to the door, I put on my makeup and straightened my hair, while telling myself that it didn’t matter what I looked like because I wouldn’t be at Grant High for long. Even so, I was too well trained to leave the house without looking my best. Too bad it was for no one but myself.

With time to waste, I poured myself a glass of milk and shuffled to the window to look outside. White smoke streamed past Tomas’s Taqueria. Wait, smoke? On the street?

“Oh my God!” I yelled. “Fire!”

“What?” Mom mumbled from under a pile of blankets on the couch.

I listened for sirens. Nothing. “Under us! In the store … no, down the street. Call 9-1-1!”

Mom sat up. A moment later, she snickered. I spun around to glare at her.

“Oh, Livvy,” she said.

My eyes darted back outside. Smoke zipped by like clouds on a windy day. Mom cupped a hand over her mouth to hide a smile. Wait, what? That wasn’t smoke? Blood rushed to my cheeks.

San Francisco.

Fog.

The two went together like clam chowder and bread bowls. Like cable cars and roller-coaster hills. How many photos had I seen of the wispy stuff weaving its way through the cables of the Golden Gate Bridge? I groaned, knocking my forehead against the glass. Mom giggled.

I pictured fire trucks screaming up the hill, cranking their city-sized ladders to our second-story apartment. All because a girl from Vermont had witnessed fast-moving fog.

It was kind of funny. Before I knew it, we were both laughing.

Mom went to take a shower, and I started breakfast. Cooking was a total challenge in the L-shaped kitchen. With the stove and dishwasher at perpendicular angles, I couldn’t fry eggs and put away dishes at the same time. The single wedge of counter space to the left of the burners was barely enough room for the coffeemaker.

When she emerged from the bathroom, she was wearing a cotton shirt with a big red poppy on the front and a pair of gray wool pants. I squinted, spatula in hand. She didn’t look the part of an executive pastry chef in one of the best restaurant capitals in the world. I slid the eggs onto plates and watched as she ate.

“I think I have something amazing for you to wear to your interview,” I said.

She looked down. “That bad, huh?”

“You should dress how you want to be viewed. A lot of people can’t see past the wrapping paper.”

She rolled her eyes, my words falling on deaf ears.

“How long until you have to catch your bus?” she asked.

Because we’d transferred at the last second, the high school three blocks over was fully enrolled. Grant High was the next best choice—except it was a half-hour ride away. I’d almost fallen off the couch when Mom explained there weren’t school buses to take me there. I’d have to take a city one like every other urban teen.

I glanced at the time on my phone. “It comes in fifty-seven minutes.”

She laughed. “My girl. Always so organized.”

“I still don’t have a clue what to wear.”

I reminded myself to keep things light before her interview. Too much was riding on this. I wished Mom could pick out a professional outfit. After some speed searching, I found my favorite silk top in the box that Mom used as a pedestal for her cactus plants. The careful packing paid off; it wasn’t too wrinkled. The blouse was casual, yet tailored. Conservative, but creative. And the autumn colors—well, autumn back home, anyway—would bring out Mom’s eyes.

“Now you’ll look like a real professional,” I said, draping the clothes across her lap.

She glanced down at her Birkenstocks. “My tiramisu speaks for itself.”

I handed her my low-heeled wedge sandals. “They aren’t interviewing your tiramisu, Mom.”

I couldn’t wait to show her what I’d been working on last night. I passed her the yellow folder with three freshly printed resumes, ready to go. I would have printed more, but I didn’t want her to think I had doubts about this interview.

She mulled them over in silence.

“So, what do you think?” I asked. The folder in her hand looked cheerful, full of hope.

She ran a finger down a page, printed on heavy-duty ivory stock. “How thoughtful,” she said, her voice tight. My eyes skipped from her to the folder and back again. Was she nervous about the interview? That would make sense, since we didn’t have a lot of savings left.

“You’ll do great.” I squeezed her hand. “The San Francisco food snobs are lucky to have you.”

“You’re right,” she said.

“I’m always right,” I joked.

“You’re always right.” Her voice sounded robotic. The eggs I’d downed hardened like a rock in my stomach.

“Well, I’d better get ready,” I said after a moment.

“I’m assuming you’re going to catch the bus on Sutter, since that’s closer, but it’s near the projects. Better go three blocks up and then left at Webster. There’s a stop kitty-corner to Donovan’s Deli.”

How did she know about Donovan’s Deli? Or where the bus stop was? I’d mapped it out last night on my phone, but it wasn’t like her to plan ahead. To plan at all, really.

She took in my expression. “I checked with Tom. He told me which streets to avoid.”

Well, at least she was in touch with him. That was a good thing. I eyed the coffee table. The list of local AA meetings was where I’d left it.

Mom picked up her briefcase and flew out the door. From the window, I watched the fog wrap around her like a puffy co

mforter. I waved, but she couldn’t see me through the haze. She pulled the folder out of her briefcase and tucked it under her arm, then jaywalked across Fillmore. When she reached the other side, she stopped. I watched as she lifted the resumes I’d made and, with no hesitation, dumped them into the trash can.

CHAPTER

THREE

MOM STROLLED UP THE STREET LIKE A PERSON with nothing better to do than window-shop on a brisk summer day.

I swiped some money off the table and ran out the door, taking the stairs three at a time. At the corner, I waited for the light to turn. Come on! When it changed, I darted across the street to the trash can and reached in. The folder was drenched in soda. I dropped it and wiped my sticky hands down my shirt.

I didn’t understand why Mom would throw the resumes away. Didn’t she want a job? I considered all of our tourist ventures this weekend. Sure, it had been fun, but fun was expensive. Was I the only one who cared about our dwindling bank account?

I looked around but couldn’t find her. With only eighteen minutes left to catch the bus to school, I jogged up Fillmore to search the cafés. My face began to sweat, and then freeze, in the cold morning air.

A bus hissed to a stop in front of me. If I rode it to the top of the hill, I could cover Fillmore faster. She couldn’t have gone far. As soon as I found her, I’d make her explain—even if it was risky to push her, like Tom had warned. I took a deep breath, trying to still my jumbled thoughts. Maybe this was a misunderstanding. I didn’t even know her side of the story. Whatever. I wanted answers. And after the time I’d wasted on those resumes, I deserved them. So I climbed on board.

Looking for bus fare, I reached into the pockets of my … Oh, crap—pajama bottoms. Worse, my South Park ones. The bus driver scowled at me as I pulled out the wrinkled five-dollar bill from home.

“Do you have change?” I asked.

He waved me back, grumbling incoherently. Didn’t he want me to pay? I stuffed the money back into my pocket. Two girls with matching ponytails looked at me and giggled. My face flared brighter than the Day-Glo plastic seats. The bus jerked forward, careening me into the pole. I grabbed hold of it and spun around to land in the last available seat.

Maybe Mom had a decent reason for tossing the resumes—like there was an error that needed fixing. A mistake I’d missed that she’d caught? Unlikely. But what other reason could there be? Maybe she’d moved us out here because of a guy. Nah. Mom couldn’t keep a secret—not when she was excited about something. Anyway, she knew I’d be thrilled if she met someone. Grateful, because then I wouldn’t have to take care of her by myself.

As the bus lumbered up the hill, I scanned both sides of the street. A woman hobbled onto the bus, a protective boot on her left foot. I stood up, sliding between two burly men with briefcases. She smiled gratefully and lowered herself into my seat. I ducked down to peer out the window. There weren’t any stores near the top of Fillmore, just houses. Where was she? My time was almost up. I didn’t want to wait the rest of the day to confront her, but I couldn’t be late for school. I was always on time. Always.

I closed my eyes as the bus rolled past D & M Wine and Liquors. Checking might be bad luck. With that thought, my stomach clenched, my palms grew damp, and my heart began to pound in my ears.

The woman who took my seat asked, “You okay, honey?”

“Uh-huh.” I dropped my chin to hide my face. Her toes, each nail painted a different color, peeked out from her bulky boot. Rainbow toes, dotted with smiley faces.

A man tugged a wire that ran above the window. Immediately the number 22 slowed. I had to get off, too, so I did the same.

“Heard it the first time,” the driver said, frowning in the rearview mirror. The doors swung open and I ran off, shivering on the sidewalk as the bus squealed down the other side of the hill.

From up here, I could see all of Fillmore. Everything, and everyone, except my mother.

CHAPTER

FOUR

ON THE BUS RIDE ACROSS TOWN, I’D NEVER FELT MORE alone. Who knew where my mother was. Who knew where I was going, either. To school, apparently. A school. Not my school. And not with my friends.

As we crossed Market Street, I checked the time. Because of my mother, I’d missed the bus that gave me a fifteen-minute buffer to find my first class.

I stared out the window, thinking of my friends, already a few days into junior year. That’s when I realized the date. I’d missed the Third Extreme Party in Audrey’s backyard on Saturday.

I looked at the people on Castro Street, donning sweaters in August. In Vermont you could have a pool party long after the sun had gone down.

Last year’s Extreme had been the best. For me, anyway. Though Sean and I didn’t make it official until later in the year, it was the first time he spoke to me.

As the bus stopped to let a passenger off, I pressed my nose against the window and smiled, thinking about the “Dress Down to School Challenge”—a fancy name for skinny-dipping in Audrey’s infinity pool.

“Livvy, what the hell?” Candace had yelled from the pool, her breasts skimming the top of the water. “Get in here!”

“I’m eating,” I’d called back, clutching an enormous, purposefully timed bowl of potato chips. My two best friends embraced fun with no excuses. Me? Not so much.

Candace, as always, had her bullshit monitor perfectly calibrated. “Put that food down and strip!”

And then I’d heard the voice. Smooth. Melodic. Achingly familiar. “Leave her alone, Candace. She’ll go in if she wants. We’re talking, okay?”

Sean Holmes. Crush since month one of freshman year. Varsity baseball player. Sexy smirk. He was single for a few minutes each year, until some new girl snapped him up like a parking spot on Fillmore.

“Um, thanks,” I’d told him, grateful that the dark hid the firestorm in my cheeks.

I couldn’t tell if we had talked for five minutes or twenty. All I knew was that by the time he walked away, the temperature had dropped, Audrey was demanding someone fetch her a sweater, and people were running from the pool to the house under shared towels.

The bus jerked to a stop, arriving in reality. Everyone unloaded. I followed them up the street, both wanting and not wanting to find the way to my new school.

Instead of three buildings sprawled across generous acreage, like my school back home, Grant High was a cement rectangle five stories high. Stairs led up from each of the corners, with one elevator marked, Handicapped Use Only! and the other, Out of Order. I stared at the maze, trying to figure out which staircase would bring me closest to Algebra 2 on the third floor. Finally I picked the smartest-looking student and trailed behind. As I emerged from the stairwell, some girls were standing next to the water fountain, babbling about party hookups, summer boredom, and the endless amount of vacation homework that a lit teacher had assigned.

God, I missed my friends.

By the time I found Room 24, there was only one seat left. The boy sitting next to me swiveled my way. “Ready or not, here I am,” he said, offering his hand. “Franklin D. Schiller.” He emphasized the middle initial.

Franklin D. was as large as a lineman on a football team, but he looked more like the anti-jock type. The mass of brown curls on his head added inches to his height. I took in his black T-shirt, which read, C8H10N4O2.

“That stands for caffeine,” he said, catching me looking. “The elixir of the gods.”

Candace’s voice popped into my head: For a kid like that, “popular” is nothing more than a sixty-one-point Scrabble word. It was one of her favorite lines.

“Where’s our teacher?” I asked.

“Harrison’s notoriously tardy,” he said. “Hypocrisy, day one. It’s what makes high school great.”

I wasn’t sure if I was supposed to laugh or not, so I checked my schedule for the fifteenth time.

“And you are?” he prodded.

“Livvy Newman,” I said, my mind on Mom again. She couldn’t have had time to

print out more resumes. I wondered if the interview had been canceled and she’d been too embarrassed to admit it.

Franklin D. asked some questions about my past. I kept my answers brief, in part to avoid tripping over general cluelessness about why we’d moved here.

Mr. Harrison scurried into the room. He dropped the slab of a textbook onto his desk to wake us up. As he introduced himself, I rehearsed what I planned on saying to Mom when I saw her. In my head, the conversation would end with, “You’re right, Liv. Let’s go back to Vermont.”

I hid my phone in my binder to check my social media. Sean, Candace, and Audrey had updated in the past hour. Standard complaints. Nothing about me. It was like I’d bungee-jumped off the face of the planet.

When Mr. Harrison wasn’t looking, I added a post: Some nice people showed me around my new school. Love my classes! Of course, it was only first period, but I suspected my East Coast friends wouldn’t connect the dots. I hit Send, convincing myself it was better to be a liar than a loser.

C-Lunch didn’t start until the ridiculously late hour of one thirty. To avoid the cafeteria scene, I left campus. I trailed behind a small crowd to 24th Street and parked myself on a bench, where I picked at the walnuts I’d grabbed while rushing out of the apartment this morning. Through the window of Joe’s Diner, I watched a waitress deliver sweet potato fries wrapped in a newspaper cone. My mouth watered.

Maybe I was worrying too much about money. If Mom got a job, we’d have money soon enough. Without giving myself time to think, I jumped to my feet and strode into the coffee shop next door. It turned out that a medium mocha cost a dollar more than a mega-cup size at Gourmet City. One sip later, I felt an overwhelming urge to return it. California coffee tasted different. Like money dwindling away. Like eviction. Like sleeping under an overpass, covered with a blanket of fog.

Stolen Secrets

Stolen Secrets