- Home

- L. B. Schulman

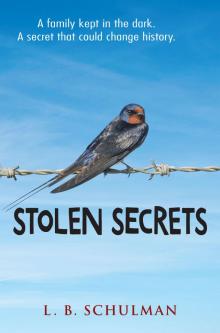

Stolen Secrets Page 13

Stolen Secrets Read online

Page 13

Oma cocked her head. “You’re a Jew.”

“I told you he was Jewish,” I said, embarrassed by her abruptness.

“So am I! I wear a Jewish star on my coat,” she said.

Franklin D. seemed to take her dementia in stride. “I hear we don’t have to wear those stars anymore.”

Oma stilled like an animal hearing a lion approach through the weeds. “Quiet! The nasty bastards are coming.”

“Who?” I asked.

“The ground is frozen, and my feet are bare, and that guard might pull out her whip.” She reached under her sweater for the necklace and tilted her head. “Do you know where my shoes are, dear?”

“They’re on your feet,” I said.

“And my necklace? Have you seen it, Livvy’s friend?”

“It’s around your neck,” I said, stroking her arm. “It’s okay, Oma. You’re safe.”

“Not that one! The other one! My pearls. Where are my pearls?”

Oh no, not this again.

“What do they look like?” Franklin D. asked. I moved behind Oma and shook my head, hoping he’d get the message. Don’t ask, divert.

“They sneak in during the night while I sleep,” she whispered, her fingers clawing at the throw pillow. “They steal my jewels for money.”

I shot Franklin D. a look. What did I tell you? Following Oma’s logic was like trying to track a shooting star.

“What was it like in the concentration camp?” Franklin D. asked gently.

I winced. That kind of question could send Oma into a rage.

“I was in the hospital, and I was so sick.” She grabbed her throat. The dramatic choking sounds sent Franklin D. from the room to retrieve a glass of water. Oma twisted her head away, refusing it. “Why is it so cold in here?” she asked him. “I want to live! But the nurse says, ‘Take this food and eat it, or there’ll be no prayer for you at all!’ I have to listen to her, or I’ll die, like that sweet little girl.”

“What girl?” I asked. “Your sister?”

“There is no sister! We died a million deaths!”

Oma looked on the verge of collapse. Why had I brought Franklin D. here? But then she slid a hand around his arm and tried to pull Franklin D. toward the bookshelf. He glanced over his shoulder to let me know it was okay.

“Sorry,” I mouthed.

Oma reached for the middle of the second shelf. She pulled out The Hunchback of Notre Dame and flipped through its pages, then discarded it for Ivanhoe. On the third shelf, she grabbed hold of The Scarlet Letter, shook it out like a towel at the beach, and threw it behind her. It hit the wall and slid to the floor, the spine broken.

“Oma, stop it!”

She started moving quicker, tossing books off the shelves. Franklin D. hopped out of the way to avoid being hit by a Dickens anthology. When Oma reached for Sense and Sensibility, her hand moving in for the kill, I grabbed her wrist.

“I have to find it!” Oma cried, ripping her hand free. She pulled Wuthering Heights off the shelf and sent it flying like a Frisbee. Dust flew out of its pages.

“Find what?” Franklin D. asked.

I pointed to the half-empty shelves. “Do you notice anything about these books?”

“Yeah, they’re really old.” He sneezed.

“Bless you. No, I mean the books were arranged in alphabetical order. By title. Well not anymore, obviously.”

In a strange way, I found my grandmother’s organizational system to be comforting. I had an overwhelming desire to protect the order of her world, even if Oma seemed intent on destroying it. I knew if it weren’t for this disease, she’d be appalled at the mess she was making.

“Look for my journal,” Oma pleaded to Franklin D.

I moved in front of the bookshelf, blocking her access.

“Gretchen’s in my way, damn it,” she said with a scathing glare that made me step to the side.

“You have a journal?” Franklin D. asked her. “Somewhere on this shelf?”

“The nurse hid them so no one will get in trouble,” Oma whispered. “You’re Jewish. I want you to take it back for me.”

“Take it where?” he asked.

“Where it belongs!”

My eyes darted to the bookshelf. If a journal really existed, it could tell me things I’d thought were lost to time. I could learn more than the tattered scraps of the past that Alzheimer’s had left behind.

Franklin D. said, “Sure, I’ll look for you, Mrs. Friedman. Sorry, Oma, I mean.” He turned away so he could wink at me without her noticing. “Excuse me, Livvy, I’m on a mission.”

I moved out of his way, relieved that he was handling the situation. “Thank you,” I whispered.

“Thank you,” Oma echoed.

He pulled a book off the shelf and flipped through the pages for anything unusual. Oma tilted her head, gazing at him. On second thought, maybe it wasn’t coyness. She looked like a kid who’d been caught with a hand in someone’s wallet.

Franklin D. worked his way through the shelf, then moved on to the next one. He fanned through the pages of each book. Second shelf from the bottom, a scrap of paper floated out from Pride and Prejudice. Franklin D. handed the leather-bound book to me and bent down to retrieve the old page. I held the book upside down and three more sheets of paper slipped out into my hand, each a few paragraphs long and written in a foreign language. I went back to the beginning to check for more but didn’t find any.

“Read it!” Oma’s tone made the two innocent words sound like expletives.

“We can’t read it,” Franklin D. told her. “It’s in another language.”

“Dutch,” Oma said.

“Can you read it to us?” he asked.

She stared at the papers in his hand, her lips pursed with disapproval. “Can’t. Don’t know how.”

Alzheimer’s, late stage. Loss of ability to read. Not the kind of fact I wanted in my head right now.

“My hair is falling out,” Oma whimpered. “Soon I’ll be bald. The lice will move to my armpits. Behind my ears. Irma says, ‘Wash outside or you will die, dirty Jew!’ She snaps her whip and calls her dogs.”

“Who’s Irma?” I asked. But this question, like all the others, earned me a blank stare.

“The war is over now,” Franklin D. said.

“What if they come back?” Oma asked.

He turned his thumbs to his chest and sucked in air, puffing himself up like a superhero. “I’m a big guy, which means I’ll kick their ever-hatin’ Nazi butts, okay?”

I started to laugh but reeled in my reaction, reminding myself that it wasn’t possible for Oma to find humor in the subject. To my surprise, she stayed calm, gazing at Franklin D. as if she was waiting for the next great thing he was about to say.

He laid the papers down on the desk beside her. She jerked back. “Take them away.”

He picked them back up as his phone pinged. I glanced at the clock. It was almost time for him to go to the restaurant.

“My friend has to go now,” I told Oma, wishing it wasn’t true. Franklin D. was insta-Valium for my grandmother.

“Good-bye, Oma.” He swept his lips across her cheek.

And there it was, Oma’s smile, in all its glory. The sun breaking through the San Francisco fog. The sight of it stunned me into silence.

“I’ll walk him to the door to say good-bye, but then I’ll come right back, Oma,” I said.

“Is it nap time already? Vickie says I need to take three a day.”

Did she forget that she’d just woken up? “Not yet. Are you hungry?”

“I don’t want your turnip soup. It’s too watery!”

“Vickie told me that you had a quesadilla earlier. You don’t have to eat anything else if you don’t want to.” I felt a twinge of empathy for Mom and all she’d gone through while taking care of Oma. Then again, she hadn’t thought of me when she’d turned her back on sobriety. With that thought, the feeling vanished.

Oma’s eyelids sagged. I grabbed her hand before she

fell asleep standing up. Franklin D. waited by the front door as I led her down the hall to her bedroom. It was hard to tell, but it seemed like she was sleeping more every day. It was almost six thirty, which meant she’d probably go down for the night. I knew I should feel happy for the break, but I wasn’t. It felt like another day lost.

When I came back, I said, “I’m sorry we didn’t get to practice for the debate.” It seemed like I was apologizing a lot these days.

“No worries.”

We headed down the hallway. When I flipped the light switch, the overhead bulb flared, then went dark. I glanced over my shoulder, squinting into the shadows. What if they come back? Oma had said. I walked faster, eager to reach the light of the foyer.

At the door, Franklin D. glanced at the pages in his hand. “Do you mind if I take these with me? I bet there’s a Dutch dictionary online.”

“Yes,” I said after a moment. “That’s a good idea.”

APRIL 1946

The tattoo parlor was at the end of a dark alleyway that stank of popcorn and urine. Though it was midday, the buildings blocked the light, laying shards of shadow at her feet. Adelle crossed her arms as she aimed for the wood door at the end, then thought better of the defensive posture. A woman alone in Manhattan could be easy pickings for a hooligan. She drew her shoulders back and tilted her head, leading the way with her chin.

A window from the back of an apartment, several feet above her, slammed shut. A bag of trash landed on top of a battered metal can, ejecting a jar of grape jam and a rotten cantaloupe. Within seconds, a stray cat showed up to investigate.

Adelle faced front again, walking as fast as her high heels would allow until she reached the entrance. A sweet, incongruous chime announced her arrival. The man, no older than her, perched on a stool beside the doorway. He shoved the girlie magazine in front of him under a small stack of old Time magazines. With a shudder, she averted her eyes from the cover on top, a bloodred X stamped across Adolf Hitler’s face, announcing the Führer’s death.

“I called an hour ago? About a tattoo?” she said.

He cranked an eyebrow, so she clarified, “… on my arm. Right here.” She gave him the design. It wasn’t art, but it didn’t need to be. “This is what I want.”

He glanced at it, then let his eyes roam up her blouse. It gave her the creeps. She knit her arms across her chest to block his stare. “That’s it?” he asked.

“That’s it exactly. Two inches long and one inch thick,” she said, careful to keep her voice matter of fact. Her wedding day was in two weeks. There was little time to waste. She had a meeting with the florist at five, and after that, the caterer.

He laughed. “Sure thing, boss.”

She reached into her handbag, pulled out the fee, and slapped the stack of cash on top of the magazines. There, now she didn’t have to look at that horrible X anymore.

The man’s laugh revealed crooked teeth stained from chewing tobacco. “I don’t see too many dames. Sailors, Mafia, lovesick fatheads, yeah.”

As he rambled on, preparing the tools, she thought of her fiancé. She imagined Herbert’s face as he peeled off her wedding gown, seeing her tattoo for the first time. The sacrifice was more than a declaration of the past; it was necessary for love, a reminder that there need only be a present and a future to ensure happiness.

“You know this is gonna hurt like the dickens, right, sugar?”

He was seeking a reaction, but she had no intention of giving it to him. “Get on with it, please,” she instructed, rolling back the sleeve of her blouse to offer her arm.

CHAPTER

SIXTEEN

AT EIGHT ON SATURDAY MORNING, VICKIE FINISHED her shift. The front door slammed, which was her way of letting me know it was my turn. I pulled up on my elbows, listening for Oma. Whew, she’d slept through Vickie’s wakeup call. I dropped my head back onto my pillow. I should get up to make breakfast—Oma liked her eggs soft-boiled—but I couldn’t pry myself from bed.

My phone rang, startling me. I rolled onto my side and squinted at a familiar number on the screen. “Hello?” I croaked into the receiver.

Franklin D. said, “I figured you were up.”

“Sort of. Isn’t eight kind of early to call?”

“Twelve minutes after eight,” he clarified.

“I hope you’re not worried about the debate. We did fine, considering we didn’t have much time to practice. That was my fault. Sorry.”

“No, it’s not that. I need to talk to you.”

I pulled back up to a sitting position and leaned against the headboard. “I’m listening.”

“Actually, I’m in the area. Like on your porch. I didn’t want to ring the doorbell in case your grandma was still sleeping.”

On the porch? Geez. I ran my fingers through my hair. “I’ll be right out.”

The door wasn’t even fully open when Franklin D. blurted out, “Online translators are modern torture devices, so I asked around. Turns out my uncle’s mechanic speaks Dutch. I was going to see if you want me to ask him to interpret the journal …” He shifted from foot to foot like it was cold out. It looked to me to be a gorgeous October morning. The sun, peeking over the apartment buildings, promised T-shirt temps.

He followed me into the living room so we wouldn’t wake Oma. “I was able to figure out a few words on my own,” he told me. “About two-thirds down the page on one of the entries, it said, ‘De meisjes van Frank.’ I’m butchering the Dutch, but—”

“What does it mean?” In the shadowed light, the old room felt like a fragment of the past being kept on life support. I parted the drapes to let the sunlight in, even though Vickie would close them as soon as she got the chance.

“According to the dictionary, ‘Frank girls.’”

I turned around to stare at him. “Frank girls?” For all I knew, there were many Franks at Bergen-Belsen. But girls? Frank girls couldn’t be nearly so common. “You think it means Anne and her sister, Margot? They died right before Bergen-Belsen was liberated.” It was clear from his expression that Franklin D. had already made the connection. His point slammed into me full velocity. “You think that Oma knew them? That she actually wrote about them in her diary?”

“If this mentions Anne Frank, it could be an important document. Like historically important,” he said. “As in, the entire world may be wholly interested.”

“Are they mentioned in more entries?”

Franklin D. shrugged. “Can’t tell. Whoever wrote this used first initials instead of names, probably to protect people’s identities in case the pages were found. But there are some that start with an A, and a few with an M, I believe.”

“That’s not exactly proof,” I said. “I mean, there’s Adelle and her sister, Margaret, for example.” I was struck by the coincidence. My grandmother and her sister shared the same first initials with the Frank sisters. Maybe that had been enough to bond two pairs of sisters.

“I thought your mom said that Oma only had a brother,” Franklin D. said.

“Yeah, well, she also said that my grandmother was dead. Hey, what’s that mechanic’s name, the translator guy?”

“Dan.”

“I think you should put Dan on the job,” I said. “Right away.”

He grinned sheepishly. “Already have. Figured you’d say that.” He peered at me through lashes a shade lighter than his eyebrows. The early morning sun deepened the soft brown in his eyes. They were the color of the mahogany vase sitting on Oma’s kitchen shelf. Wait, why was I thinking about Franklin D.’s eyes?

“I’m glad you went ahead.” My voice squeaked. What was my problem? This was Franklin D., king of goofiness. “How could Oma have kept a diary in Bergen-Belsen anyway? I don’t think that was a Nazi-approved activity.”

“I had the same thought,” he said. “But a woman named Hanna something or other wrote a diary, and I think there were a few others, too.”

“If only I could ask Oma about this.” If only she could be l

ucid for more than a few seconds.

“Dan says he might be done by next weekend.”

“Why don’t we go see him now? Maybe he’s had a chance to translate the first entry by now,” I suggested.

“He says he won’t have time for a few days.”

A piercing call came from the hallway. “Where is everybody? Did I die and go to hell?”

“Most people say heaven at the end of that phrase,” Franklin D. said.

I shouted back, “Be right there, Oma.”

“Quack, quack!” Oma called from inside the room. She sounded more like a barking seal than a duck.

The disease made her do silly things sometimes, but I didn’t mind. The silliness made her seem younger. Spirited. I couldn’t help but smile. I opened the door, glad I felt comfortable having Franklin D. around this time. Oma stepped forward, folding her arms around my waist. I hugged her back and thought about my mother’s comment: She can’t even remember what a rotten mother she was. Maybe so, but she wasn’t a rotten grandmother.

Oma eyed Franklin D. “What’s that boy’s name? I like the looks of him, but he doesn’t have a name.”

“That’s my friend, remember? Franklin D. Sch—”

I stopped, not wanting to go through the “Is he Jewish?” conversation again.

Franklin D. spread his arms out. “Ready or not, here I am!”

I laughed, recognizing the dorky phrase he’d used on me a few times.

“You’re a chatterbox!” she said, nudging him in the side with her elbow.

“I’ve been accused of worse.”

It seemed that Franklin D. genuinely liked her. That wasn’t a huge surprise. He preferred people who were different from everyone else.

“Hey, you’re still in your pajamas,” I said to Oma. “Why don’t I help you—”

“Don’t touch me!”

“Oops—I forgot. She never lets anyone help her,” I told Franklin D., forcing a smile for Oma’s sake. I didn’t want to start the morning out wrong. “She gets dressed by herself.”

“Nothing wrong with that. I always insist on dressing myself, too,” Franklin D. said.

“Maybe we shouldn’t encourage her,” I whispered.

Stolen Secrets

Stolen Secrets